My aim in this digital project is to evaluate the data, and use it to substantiate a claim that declares that language or rather the diversity of language (in Lebanon particularly) is what allows for there to also be a shaping of identities. I will be looking at the ways transnational theory and Lebanon’s history of colonial powers and mandate systems have affected the different kinds of educational systems that have been laid out for the country, and the ways that has allowed people of a certain economic or social class to form identities that coincide with the languages they use. This, I hope, will be evident by tracing the books the interviewees read, mostly during School Time (ST), and forming connections with what languages the books were in, and what year the interviewee graduated.

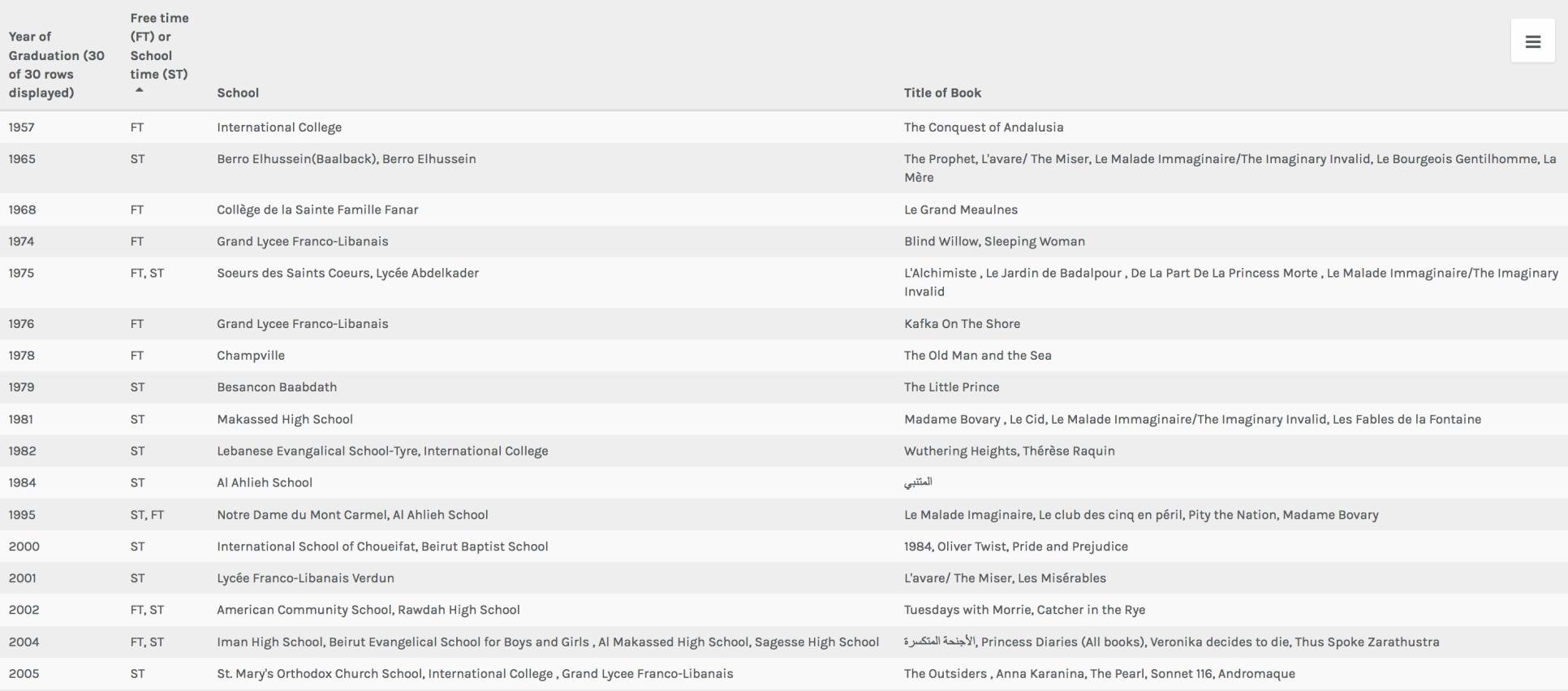

Using a Palladio table, I was able to organize the data with specific subjects I had chose. Such as: Year of graduation, Free Time (FT) or School Time (ST), the School the interviewee went to, and the title of the work of literature they read (in the language they read them in):

The information is organized in a timeline from the earliest year of graduation, and incrementally moves towards the latest year of graduation. It is also important to note that these graduation dates are restricted to graduating from High School. From 1957 till 2005, I would say there is quite a diverse array in the languages used (also mostly during ST). It is mostly French, but there is also Arabic, and some English. I would also argue, that if one takes out the FT option, and only considers the ST option, there would be less English novels or works of literature to consider.

As the list progresses, one can see how more and more English is integrated into school curriculum. Above, (Graduation year 2006 till 2014) almost most, if not all of the books read during school time are in English or include Classic English works of literature.

The same can be said for years 2015, and 2016.

The same can be said for years 2015, and 2016.

Deanna Ferree Womack, in her article: “Lubnani, Libanais, Lebanese: Missionary Education, Language Policy and Identity Formation in Modern Lebanon” notes in her discussion about the language policy in the late Syrian Protestant College, that “the earlier classes of the College were instructed through the medium of Arabic, but more recently English has become the language of the Institution in all Departments, the first class taught through the medium of this language in the College Department, having graduated in 1880” (9).

I would like to point out that I am not interested in advocating for language policy reform, or that “we” as a country have become too “westernized” – whatever that term may mean. I am simply observing the data, and making a statement substantiated with historical evidence – so that I can contextualize the data that we have gathered. I am not interested in saying whether this is a good or bad thing, because an argument like that would quite frankly be irrelevant to a much wider claim about globalization or western colonialism. And even when talking about these issues, it is important not to take away the agency of those that have been colonized i.e. us.

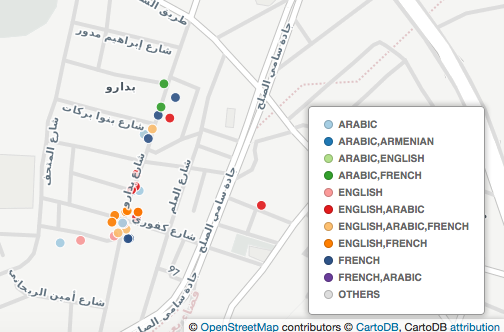

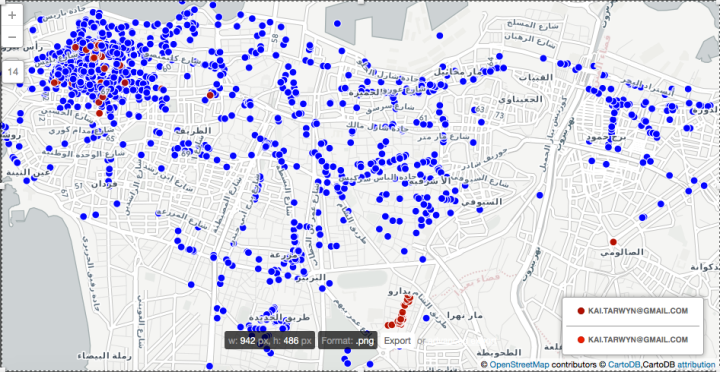

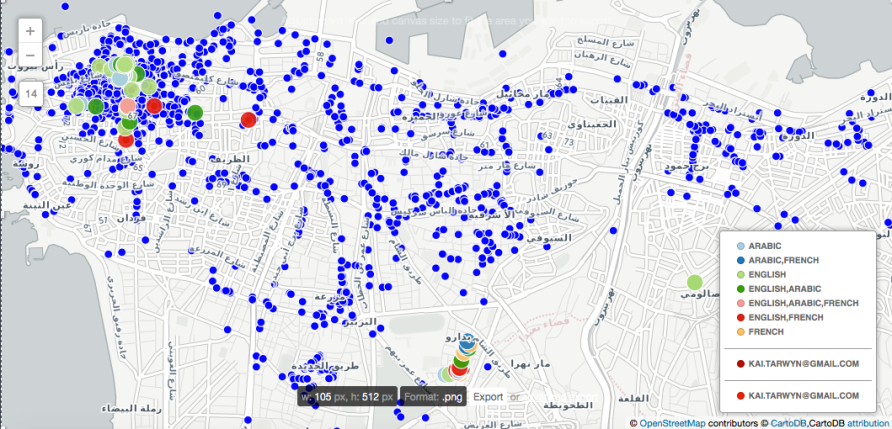

The more I looked at the data, I saw connections between the highschools that the interviewees graduated from, and the language of the books they read in school:

Of course, this would seemingly come as a simple rather straight-forward observation, but I’m interested in how language and identities are formed in light of something like this.

Womack also writes, “[t]he majority of students and their families, however, demanded instruction in English and French because of the wider economic and intellectual horizons these languages could provide. Fluency in a second language offered a spiritual or cultural connection to the West, but students also valued Arabic” (17).

This isn’t to say that the languages of colonial powers like French and English aren’t useful, or that they shouldn’t be useful – it’s that they are. And my question is, could we change that? Do we want to change that? What does it say about the way the world works? About transnationalism? And what does it do to the ‘authenticity’ of our identities, if there is such a thing?